The old Dallas Central Library building — along with the Statler Hilton next door — was built as a showcase of modern architecture for a city booming during the 1950s. Representing the best block of mid-twentieth century architecture in Dallas, the long-abandoned building at the corner of Harwood and Commerce still holds many surprises.

History of the Site

The Dallas Public Library’s first structure was built on a city-owned lot at the corner of Harwood/Commerce with $50,000 donated by Andrew Carnegie. The new French Renaissance-designed Carnegie Library opened in 1901 with 10,000 books, an auditorium and the city’s first public art gallery. But the library foundation’s lack of funds and city’s rapid expansion led to poor maintenance of the structure; as early as 1927 there were calls for a replacement structure. By the 1940s the 2nd floor was in danger of collapse. An argument erupted over which city (Dallas or Oklahoma City) had the worst library in the nation.

By 1950 citizens and officials demanded a replacement for the dilapidated structure, and it was suggested a new library be built at the Civic Center site rising along Marilla/Akard Street (planned to house a new City Hall and auditorium). This site was favored by the City Plan Commission because it was closer to the center of downtown, accessible by automobile and had plenty of room for future expansion. When plans for the Statler Hilton were announced, the value of the land increased and officials began receiving offers for the land. The Statler offered $400,000 for the plot (for an additional wing of their new hotel) and another offer of $500,000 was presented. There were also arguments to relocate the library into a renovated City Hall across the street. Both of these would have allowed the library to remain — rent-free — until a replacement structure was finished. The Library Board, however, pleaded that the new library remain on the current site. This ignited arguments by everyone involved. After 3 separate decisions by City Council, the matter was finally settled in 1953 with a vote to build the new library on the Harwood/Commerce site.

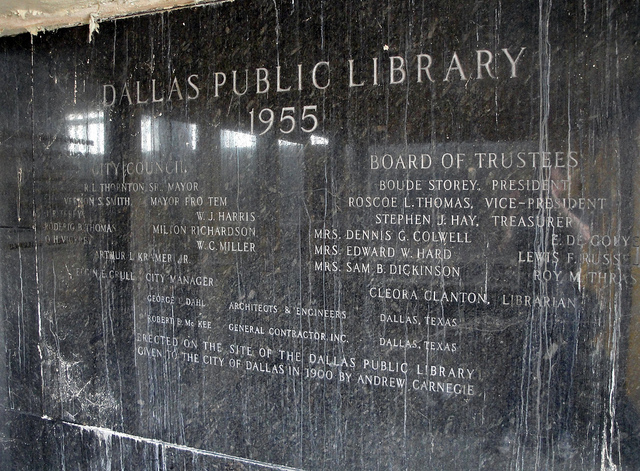

Construction proceeded quickly, and the library’s collection was relocated to Union Terminal. The Carnegie Library was demolished and an additional 50’ wide plot along Wood Street was purchased, giving the L-shaped footprint. George Dahl, one of Dallas’ most prolific architects, designed the new building to fill the entire plot of land. Feared it would be a “lean-to” adjacent to the new Statler Hilton, the structure was designed to compliment the modern façade of its neighbor while having a dramatic presence of its own. The glossy black marble façade created a solid front along Commerce while a wall of windows along Harwood provided ample natural light inside.

The new library was designed much like a modern department store of the era. On the ground floor was the popular collection, young-adult, literature & history, community-living and family-living departments. Science and industry collections were housed on the mezzanine above. The children’s department, Texas collection, fine arts and fashion departments were on the the third floor while the fourth floor featured exhibit areas, work rooms, and a rooftop terrace. The basement level contained reading rooms for newspaper and magazine collections. And below that — in the sub-basement — was an auditorium containing 250 seats for meetings, film presentations and lectures.

Controversial Artwork

The new building was the first public building in Dallas to incorporate public art, which provided much controversy during construction. A 3,000 pound, 10×24 gilded metal screen designed by Harry Bertoia to hang above the circulation desk consisted of several hundred pieces of bronze, steel, nickel and chrome. The mural was very modern in design and Bertoia stated that it should have no name.

It is a mirror to the person who looks at it. Those who find nothing have evidently not prepared their lives and probably are very happy about it.

Mayor R. L. Thornton found a name for it — a “bunch of junk” — and public officials claimed that funds would be better used on books rather than a “cheap welding job.” As a result of the many questions surrounding the artwork, George Dahl bought the $8,700 mural and shipped it to his home — thus relieving taxpayers of their obligation to pay for it. Private citizens and the AIA Dallas then stepped in to donate money for the sculpture, and the city reluctantly accepted its reinstallation in the library. AIA stated during the process:

If the object is not a worth creative work it should not be placed in the library at all. On the other hand, if it is acceptable for use as an ornament to the building, if it is permitted to occupy the place for which it was designed, it should be paid for by the city, and neither the architect, nor one, nor a group of private citizens should be called upon, or even permitted, to pay the cost of it.

This debate and argument over artwork in public buildings was the impetus for a “fine arts commission” that would rule on artwork for all future public buildings in the City of Dallas.

For the outside of the new structure, artist Marshall Fredericks designed an 880 pound, 20-foot monumental aluminium sculpture to hang on the black marble façade of the new library. Fredericks’ originally submitted several concepts to architect George Dahl. One concept consisted of two large hands holding within them two standing human figures — man and woman — the man reaching upward and just touching a star. Another entitled “Family Group,” represented the Mother and Father teaching a small child the value and beauty of books and knowledge. “Youth in the Hands of God” represented “ the hands of God supporting Youth in its search for Knowledge through the medium of Literature.” The $12,000 sculpture was cast in Norway and took a year and half to complete. Originally, the boy in the sculpture was nude. After some convincing by city leaders, Fredericks gave the boy some pants to appease a conservative public. These pieces of art were ingrained into the architecture of the building, designed specifically for the spaces they adorned.

Changes

Both the new library and Statler Hilton — sharing the same contractor – rose simultaneously; a 1-inch gap is all that separated the buildings. The $2.5 million library opened in September 1955. Originally containing 220,000 books, the collection expanded with the growing city; by 1975 the library held over 660,000 books. Space had become so tight that hallways were used for storage and aisles between shelves were uncomfortably narrow. As the building aged a notorious leaky roof and bursting pipes added to maintenance issues. By the late 1970s the overcrowded 125,000 square feet building (with limited expansion capabilities) led to the construction of the 665,000 J Erik Johnson Central Library in the Civic Center area. Ironically, this new building contained everything the City Plan commission had recommended back in the 1950s. The old library closed in 1983 and was sold to an outside investor; once emptied it was never used again. In 1996 it was purchased by Hamsher International Ltd. of Hong Kong — owners of the adjacent Statler Hilton Hotel.

30 years later the building remained abandoned and unused, although it had been listed as a contributing structure in the Harwood Historic District. Decades of water infiltration due to the unrepaired roof rusted elevators and flooded basements. But while the lower floors harbored mold the main reading room remained largely unharmed. Previous developers announced grand plans for the adjacent hotel but were always perplexed on what to do with the library (a parking garage was the best proposal). In 2010 Richhi Developments Group purchased the building — along with the Statler Hilton — and began the clean up process. Unlike previous developers, they hope to return the building to profitable retail use and have recently acquired the original plans for the building.

When the library closed, Bertoia’s “Textured Screen” moved to the J Erik Johnson Central Library and can still be seen hanging from the atrium. The atrium also contains the original cornerstone of the Carnegie Library. “Youth in the Hands of God” was left to hang on the front of the empty structure. Originally the library planned to take the sculpture with them, but after further investigation determined that it would not be feasible to remove the sculpture without damaging the marble and affecting the City of Dallas’ sale of the building. Fredericks contacted the developer in hopes that they would sell the sculpture to him or donate it to Saginaw Valley State University. In 1993 Fredericks finally made progress but was denied removal so that the City of Dallas could be given the opportunity to acquire the sculpture (Fredericks did not object to the city acquiring the sculpture, as long as it was displayed in a suitable manner). Because of maintenance costs, the City declined to repurchase the sculpture and it was sold to the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum. Only the hooks on the black marble facade give us an idea of where it once hung.

Design

Despite years of neglect, even today the mid-century design and thoughtful layout makes the old library a striking structure. Unlike the great height of the adjacent Statler Hilton, the library is well grounded with a horizontal emphasis. The eye works its way up the crisp lines and uninterrupted facade until confronted with the prominent overhang near roof level — a visual barrier that grounds the structure with a little post-war flair. The facade along Harwood, meanwhile, is a repetitive pattern of windows divided by large aluminum fins.

From Commerce Street the building looks like a solid mass of marble and stone. There’s nothing about it that alludes to a public building or library; unlike the grand Beaux-Arts City Hall across Harwood, this building looks like a department store, bank or museum. The solid planes created a prominent background for Frederick’s sculpture and distinguished the building from its busy, pattern-heavy neighbor. As one enters the building, though, the sense of grounding disappears. George Dahl’s engineering skills are showcased in the main reading room, an expansive column-free room with large expanses of windows that allow natural light to fill the area. Even with the ground level windows (between bookcases) now covered, natural light floods the double height reading room and bounces off the coffered ceiling. The aluminum fins along Harwood direct and diffuse sunlight to fill the entire space. The light bounces off sculptured angles on the mezzanine, making it appear to float over a row of columns. The narrow staircases and thin metal railings create rhythm around the room. As one walks through the building the changes in ceiling height, integrated artwork and varying wall coverings create intimate spaces in a large public building.

The building showcases the best of Mid-Century design, embodying the modern aesthetic by balancing natural materials with scale and intimacy. Unlike modern libraries that remove themselves from the noise and activity of the city, this building boldly interacted with the street life outside. The broad window along Commerce — complete with pendant lighting — once showcased inside activity to pedestrians, while numerous planters and a rooftop terrace brought a bit of nature indoors.

Future

Walking through the structure today feels like an exploration to the Titanic… layers of rust, flaking paint and dirt cover the bones of a strong structure. Entire elevators have been corroded through, yet paper artifacts remain unmoved. As more of the building becomes accessible with cleaning and remediation, perhaps we’ll appreciate this gem a little more and see it brought back to life.

The building sits in the center of a neighborhood ripe for redevelopment. The opening of Main Street Garden in 2009 extended activity to the east end of downtown Dallas; as a result, several restaurants have opened and more are planned. The Atmos Complex — scheduled for conversion into residential units — lies directly behind the library across Jackson Street; the nearby Municipal Building will soon house the UNT at Dallas College of Law. The proposed streetcar system for downtown Dallas calls for a major transit route down Harwood Street, connecting the Farmers Market area to the Main Street District.

The lack of parking — which was always a concern even when the building was in use — is a challenge for the building’s rehabilitation, but excess capacity in nearby garages could be a solution. The private Gold Ring Garage once stood across Commerce before replaced by the park. Previous owners considered the library building only useful today as a parking garage for the adjacent Statler hotel. This lack of creativity would deprive the busy corner from much-needed destination retail forming part of a vibrant mixed-use development.

Long a desire of downtown advocates, a bookstore anchoring the building’s ground and mezzanine levels could take advantage of abundant natural light and original bookcases. The rooftop terrace could be the perfect place for a restaurant or lounge overlooking some of downtown’s best architecture. The basement auditorium could work well for a community meeting room or educational lecture room. The size and open floorplan of the structure allow many different uses; current developers acknowledge that the building could be a prime candidate for specialty retail, an office tenant, university classrooms or an academic library. While optimistic, they envision this building will be cleaned and ready for occupation in a year’s time. The preservation efforts of the development team — and creative adaptation of an unused space — would result in a functioning building that celebrates the energy and history of one of our best Mid-Century structures while infusing the Harwood Historic District with a new destination designed for 21st Century sustainability.

To view more images, visit this album. Special thanks to the Richhi Developments Group for the pre-restoration tour and Corey Rawdon for joining.

About the author: Noah Jeppson is creative designer and urbanite. As a resident of downtown Dallas for 5+ years he has been active in neighborhood policy, advocacy and preservation. To connect, find him on Twitter as dfwcre8tive.

Noah

Great article !!! It was great to meet you back in March, please don’t forget to copy me in your articles or postings.

Best regards

Francisco Arias

These are great pictures and a big help. If you have any additional photos please send them to me.

We are in the process of restoring the building. The exterior will look like it did when the building opened. Much of the first floor will stay the same too.

Thanx to the Dallas Morning News for saving this wonderful building. I remember the Central Library fondly for my many visits there as a schoolboy back in the 60s and 70s.